The recent announcement of an agreement between central government and Cornwall Council to allow for more local control over service delivery is a welcome step in the direction of decentralisation but, says Joanie Willett, it falls well short of meaningful devolution.

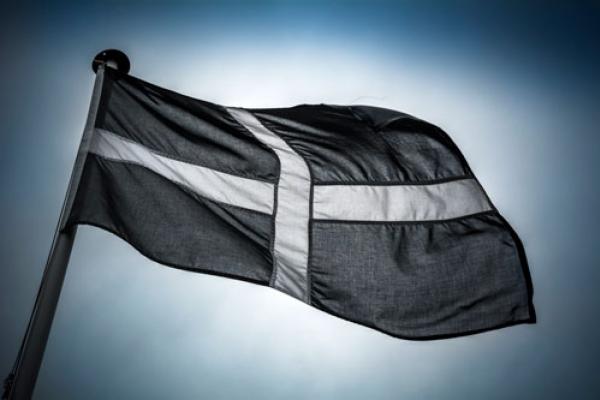

Devolution has been an emotive topic in Cornwall for decades. Campaigners have worked hard for something along the lines of the Welsh model and, in 2001, gathered a petition of 50,000 signatures in support. At the time, Regional Assemblies were very much on the British political agenda and Cornwall was keen for a distinct devolution package without being shoe-horned into a South West Assembly, stretching from Land’s End to Swindon. This was important not just because of the strong local identity in the region, but also because it is a spatial and economic periphery with a problem of chronic underfunding compared with other areas, and a strong sense that central government frequently overlooks the region’s needs.

When devolution within England fell off the agenda of central government, rather than withering away, Cornwall’s desire for devolution continued to grow and became more entrenched. When, in the aftermath of the Scottish referendum political decentralisation came back into vogue with central government, it was no surprise that Cornwall should be one of the front-runners to put its case across.

Local authorities have been encouraged to engage with what the Local Government Association (LGA) calls ‘Devo Next’. Keen to support decentralisation in order to take advantage of ‘the economic, political and social benefits to communities’ across the UK, the LGA offers support to local authorities keen to take advantage of this opportunity. This is within a context where the UK is one of the most over-centralised states in Europe, and there is a wealth of evidence that decisions taken locally are better equipped for responding to local needs.

Cornwall Council invested a good deal of effort in putting together its Case for Cornwall, which officially received backing of Council members on the 14th July 2015. In a series of consultations this was presented to the public as an important step forward in the long campaign for a Cornish Assembly. The Case For Cornwall called for measures such as the powers to develop an integrated transport network, control over all publically owned property in Cornwall (including that owned by the NHS, and the Department for Work and Pensions), and the capacity to develop integrated public health services between the NHS and health and social care. It also requested a share of certain forms of taxation raised in Cornwall, the ability to make their own decisions about how European structural funding is spent, and a range of measures to improve links between education provided and the needs of local businesses.

But is this really devolution? No legislative powers were requested, as might be expected if Cornwall were to receive anything similar to devolution in the Welsh model. Instead, the watch-phrase is ‘Freedoms and Flexibilities’ to be able to deliver public services more efficiently. Democratic accountability is also in question as the Council appears more frequently as a partner amongst many, and as chunks of economic planning are passed to the Local Enterprise Partnership. We might agree that this is a form of decentralisation, providing the capacity to make decisions locally on local issues, but falls a long way short of what we might call devolution.

Moreover, the announcement on the 17th July that Cornwall is to receive a ‘devolution deal’ arrived before the Case for Cornwall had been formally submitted, and the offer fell far short of many of the powers that the Case asked for. There is still some optimism that Cornwall might receive an enhanced offer later but there are no definite indications that this will actually go ahead. It is also worth noting that because many of Cornwall’s institutions are centralised to Cornwall-wide bodies, the region has managed to avoid the Mayoral system given in other ‘devolution’ type packages.

Does this mean that the government is serious about political decentralisation? This is less clear. Public sector cuts are set to continue, and there is a strong indication that the freedoms and flexibilities granted are expected to make efficiency savings in a tough funding environment. Further, freedoms and flexibilities are often about how central rules are interpreted locally, rather than being able to change rules to suit local conditions, and planning provides a good example of this. Frequently communities are unable to do little more than apply government policy with regards to developments, and have to follow the National Planning Policy Framework. This means that towns and parishes are often powerless to shape housing developments according to local needs, as they must contribute to national quota systems. This has led to anger and disillusionment in the political system, and a rift between different layers of governance.

What does Devo Next mean for British politics? Undoubtedly it provides the opportunities for dynamic regions to step up to the mark. However it falls a long way short of a properly negotiated constitutional settlement to address the strained relationship between the centre and the regions.