How interest groups lobby on multiple levels to influence national laws in Germany

By Florian Spohr, Patrick Bernhagen, Krispin Krüger and Felix Goldberg.

When interest groups want to influence national legislation, they typically focus on federal ministries and parliament. But in countries with multiple layers of government, lobbyists have additional options. Regionalization and European integration have created various channels for political communication, allowing groups to pursue influence across subnational, national, and supranational tiers of authority.

Understanding German federalism

Germany offers a fascinating case for studying such multi-level lobbying as its pronounced federalism and European Union membership creates numerous access points for interest groups.First, the country is organised as a federal republic with 16 states, known as Länder, with their own governments, parliaments, and significant policy-making powers in federal legislation. Furthermore, via the Bundesrat, Germany's upper chamber, the Länder have a veto power in federal legislation that directly affect them. This gives regional governments substantial leverage over national policy—and makes them attractive targets for lobbyists.Secondly, Germany is deeply embedded in the European Union. Between 50 and 80 percent of national legislation is based on EU regulations. This makes the EU Commission, Parliament, and Council attractive venues for lobbying national policy-making as well. Thirdly, the regional and EU-level are intertwined. The Länder have their own representations in Brussels, offering another avenue for domestic interests to influence policy.

Mapping routes to influence national legislation

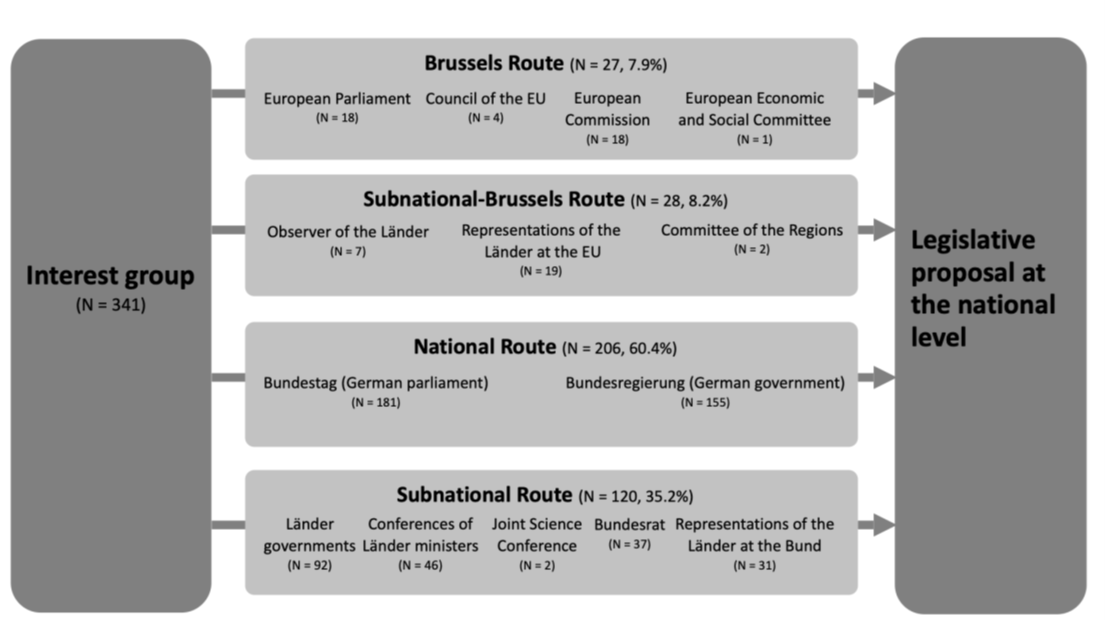

Adapting Justin Greenwood’s (2017) argument about routes for influence-seeking in the EU to national policymaking in a multi-level system, we identify four distinct routes that interest groups can pursue to influence national legislation (see Figure 1). The national route involves lobbying federal ministries and the Bundestag directly. Furthermore, we argue that interest groups can pursue three distinct multi-level routes to circumvent the national executive and parliament: The Brussels route targets EU institutions such as the European Commission and Parliament, which research has shown are lobbied by roughly 80 per cent of national associations at least occasionally. The domestic subnational route works through Länder governments, the Bundesrat, and ministerial conferences where Land ministers coordinate their positions. Finally, the subnational-Brussels route uses the Länder's EU representations and the Committee of the Regions to reach European decision-makers—venues that facilitate exchange between regional stakeholders and EU institutions. To understand how interest groups use these routes, we surveyed 341 organisations active on 23 federal laws in 2019.

Figure 1: The four routes to influence federal legislation in Germany.

Key findings

Our analysis reveals several important patterns. First, multi-level lobbying is not a fallback strategy for groups that lack access to federal policymakers. Confirming earlier findings by Beyers and Kerremans, we found that it complements rather than substitutes for national-level engagement. Interest groups that lobby at the European or regional level are also active at the national level.

Second, the domestic subnational route is far more popular than the Brussels route. While less than 10 per cent of groups contacted EU institutions to influence federal legislation, over a third pursued a subnational strategy. The most frequently used venues on this route were the Land ministers' conferences (Fachministerkonferenzen), where the 16 states coordinate positions before formally introducing amendments through the Bundesrat.

Our statistical analysis of the drivers of route choice produced some unexpected results. We expected that groups would take the Brussels route when they lacked sufficient contact with the national government or felt their concerns were not taken seriously. Neither factor proved significant. Similarly, opposition from other stakeholders (mobilization bias) did not push groups to engage in subnational lobbying.

In contrast, we found that a central driver towards the domestic subnational route is whether an interest group's home state government shares its position on a bill. Groups prefer to engage with Land-level institutions when they have a regional ally. This finding supports research showing that subnational governments themselves act as interest organisations in multi-level systems. Interestingly, whether the Bundesrat had formal veto power over a proposal did not significantly affect route choice.

Implications for understanding multilevel lobbying

These findings have broader implications for how we understand interest group behaviour and strategy. The research shows that lobbying does not operate in discrete, level-specific containers. Rather, interest groups strategically engage on multiple levels of government simultaneously, using different routes as complements rather than alternatives. This challenges what Constantelos calls the ‘implicit assumption in interest group research that political games are played at discrete levels’ (2007, p.40).

The prominence of subnational lobbying is particularly noteworthy. While much research on EU lobbying has focused on how national groups engage Brussels, this study suggests that the regional level may be equally, if not more, important for influencing national legislation. The conferences of Land ministers emerge as a crucial but understudied venue—a space where regional governments coordinate their collective response to federal proposals.

The findings also highlight the role of subnational governments as allies in interest representation. When a Land government shares an interest group’s policy position, it can serve as a powerful amplifier of that group's voice in federal law-making. This suggests that the geography of interest representation matters—groups with regional roots and regional allies may have advantages in multi-level systems that their purely national counterparts lack.

While Germany's strong federalism makes it an obvious case, similar dynamics are likely at work in other EU member states with federal or regionalised structures, such as Belgium, Austria, Spain, and Italy. Understanding how interest groups navigate these multi-level systems is essential for understanding contemporary policymaking in Europe.

Author Biographies

Florian Spohr is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Stuttgart and currently Principal Investigator of the DFG-funded research project “Populations, Access and Bias in Multi-Level-Lobbying (PABIM).” He has published on interest groups, policy analysis, and labour market policies in Policy Sciences, West European Politics, and Governance, among others. His most recent book is Lobbyismus? Frag doch einfach! (UTB, 2023).

Patrick Bernhagen is Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Stuttgart and currently Principal Investigator of the DFG-funded research project “Populations, Access and Bias in Multi-Level-Lobbying (PABIM).” He is the author or co-author of numerous articles and books on interest group politics, public policy, and political behaviour, including Corona, the Lockdown and the Media (de Gruyter, 2023, with David Kybelka), The Political Influence of Business in the European Union (University of Michigan Press, 2019, with Andreas Dür and David Marshall), and The Political Power of Business (Routledge, 2007).

Krispin Krüger is an MA student at the University of Konstanz and a research assistant at the University of Stuttgart. His research focuses on lobbying, corruption, and quantitative methods. Recently, his article “Subnational Lobbying on National Policymaking: Evidence from Germany” has been published in Governance (with Patrick Bernhagen and Florian Spohr).

Felix Goldberg completed his PhD on lobbying and political corruption. He is research fellow at the University of Stuttgart, Local Research Correspondent on Corruption for Germany at the EU Network against corruption and referent for national and international professional policy at the Architects’ Chamber of Baden-Württemberg.

This blogpost represents the views of the authors, and not necessarily those of Regional and Federal Studies, the Centre on Constitutional Change, or the University of Edinburgh.